I have a love-hate relationship with thunderstorms. As a Dispatcher, thunderstorms bring what I feel is the biggest challenge to the job. It is also a Dispatcher’s time to shine and when their pay check is truly earned, making the job fun, rewarding and incredibly satisfying.

The level of challenge sometimes surprises many people because thunderstorms have a relatively short life. Snowstorms present some challenges, but when a blizzard is present, if conditions are that bad, the airport will often shut down in advance or the airline will have canceled enough flights to where the dispatch workload is lighter. Snowstorms are easier to predict and sit over an airfield for a long period of time, so when you can’t get in, you know you’re done for a while. Thunderstorms, on the other hand, tend to pass through a location in about 20-30 minutes. Though fast-moving (average from 25-40mph, or faster!) there are multiple influences that affect the growth, dissipation and speed of the storm, making predicting the time of the storms arrival very challenging. Not to mention that storm cells may be in clusters, where an airport can receive a torrential downpour, while a neighboring town a few miles away can be dry as a bone. Try forecasting that 8 hours out!

On The Ground

When a thunderstorm passes through, more often than not, the airfield is getting shut down. Though lightning strikes on aircraft are not uncommon, they rarely cause enough damage to actually affect the flight beyond a required maintenance check back on arrival

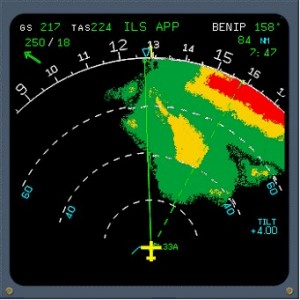

This diagram shows how an aircraft responds to the various wind changes associated with a downdraft/microburst, similar to what caused the crash of Delta 191

and maybe addressing some minor damage. The real thunderstorm threat comes from downdrafts and windshear. Sudden and major changes in wind speed and direction can mean disaster for a flight that is already in a critical phase of flight, especially on landing, where the difference between an aircraft approach speed and stall speed is close enough that wind changes could be a prescription for a stall. Last weekend was the 29th Anniversary of Delta Flight 191 , where an L-1011 trying to land at DFW hit a microburst, was unable to recover, with the resulting crash leading to the deaths of 137 people (27 did survive the crash). As with all crashes many lessons were learned and the skies are safer than ever, with a microburst crash not having taken place in 20 years.

Flight Planning

That pre-planning process is another layer in dealing with thunderstorms in terms of the routes selected. Thunderstorms tend to be at least 30,000 feet high, and can be as high at 75,000 feet, making flying over the storm simply impossible. It’s up to a Dispatcher to choose a route that can avoid, or have the best chance to avoid, a thunderstorm. However it can be difficult to know where a storm will be several hours in advance. Often, the Dispatcher will just have a choose a route that looks best. Now, I need to emphasize that this does not mean that it becomes a crapshoot that will send your plane into a thunderstorm. That simply will not happen in controlled airspace. Pilots using their weather radar, guidance from Air Traffic Control (ATC) or a Dispatcher will always help a flight avoid a thunderstorm (Note: Air France 447 happened in airspace not controlled by radar and was the result of many factors, with flying through a storm not being the largest contributing factor to the flight’s demise).

Holding and Diverting

Aside from stopping flights from departing and not allowing inbound flights to land, what do you do with those already-airborne arrivals waiting to get in? There are multiple factors here, and several players involved. First, the airspace/airfield will be closed by a thunderstorm, and ATC will assign a holding fix for the inbound flights. They will “stack” planes at different altitudes over various waypoints/fixes, and giving them the opportunity to sit in those holding patterns until the storm passes and the surrounding airspace is also clear so that the flight can continue on to its destination. But how long can the flight hold?

For most airlines, once a plane is sent into holding, they communicate with the Dispatcher via ACARS message (texting for airplanes) or air-to-ground radio (if the aircraft and Dispatcher are within adequate range of each other), informing them where they are holding, the assigned altitude, the fuel that they have on board, and the time that ATC said they can expect further clearance (EFC). From there, it’s the Dispatcher’s turn to do some math and decision making. The Dispatcher will use the given fuel and altitude to determine how long the flight can hold before they must divert to another airport. These calculations are then provided to the flight crew through the ACARS system.

Keep in mind that in the flight planning stage, it was the Dispatcher that decided how much fuel to add in preparation for such contingencies. These decisions have variables, which may limit the amount of holding fuel that can be placed on a plane, such as fuel tank capacity or maximum takeoff/landing weight limitations. Assuming that the Dispatcher put a destination alternate on the flight plan, that fuel also gets factored in, and can limit holding time, because there has to be enough fuel to make it to that airport as well (but that’s a separate article).

Once a Dispatcher determines how long a flight can remain in a holding pattern, it is decision time, and there are two big questions to ask:

1. Is the alternate that was originally planned still viable from an operational standpoint? Safety is of course the number one priority, but once that has been established, and though the airport may be legal as per regulation (weather and NOTAMs), has the airport already been flooded with diversions? Will they have staffing/service issues as a result? Is there anything that may cause the diverted flight to end up sitting on the ground at a diversion airport for hours, creating a slew of other issues for the passengers? If the answer is yes, then maybe a new alternate airport needs to be chosen, and fuel numbers recalculated.

2. Is it even worth holding? Fuel is a major expense at airlines. The Dispatcher needs to use his/her know-how to determine if, after a long period of holding and using up all of their fuel, the flight will even have a realistic chance to be cleared to the intended destination to begin with. Often, it can be better to skip the hold and divert immediately instead of waiting. The advantage is that the flight can be one of the first on the ground at a diversion airport, be one of the first planes fueled in what can be a long line of diversion flights, and be the first back in the air to recover the flight. Holding for 45 minutes to divert anyway is a huge waste of fuel dollars.

Once the decisions are made, the flight will end up diverting or holding and continuing to land as planned. The Dispatcher’s challenge is that they may have multiple flights vying for the same airport, or multiple airports afflicted by storms in a particular region. The workload piles up FAST when you have 4 or 5 planes doing laps in a hold. Prioritizing, multi-tasking and being efficient are the only ways to get through it.

Enroute Avoidance

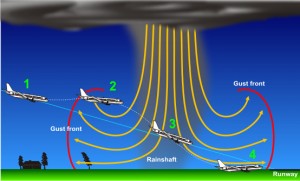

An example of Dispatcher-suggested storm deviation. The green line shows the planned route, and the pink indicates the path actually operated to steer clear of the weather

A Dispatcher’s toolbag includes various resources, namely weather radar, offering an overhead, 360 degree view that lets us see the layers of lines and cells in a storm, trends of building up or dissipation, and an overall macro perspective. The best products update every 5 minutes, which granted, could be the difference of 30 miles for an airliner. It still allows us to offer long range guidance to a pilot, specifically providing them with details on the storm (location, height, movement speed and direction), and a couple waypoints or direction on how to scoot around it. The pilot then gives that request to ATC for approval and all is well.

Inside the flight deck, they have their own weather radar, which sits in the nosecone and is forward-looking. With updates every 10 seconds, this radar allows the pilot to tilt the aim of the signal up or down, to look for weather at various heights, and to see what is ahead when climbing or descending. Its reliable range is about 40 miles, and anything beyond that distance is blurred, weak, and can be considered as “rumor” until they get closer and have a better idea.

Radar essentially works by shouting out a signal, and then listening to what returns. Whereas Jerry MacGuire’s famous line was “Show

me the money,” if he was a weather radar, his catch phrase would be “Show me the water!” This is because liquid water will best allow the signal to bounce back to the aircraft, offering the most reliable information. Though storms can climb as high as 75,000ft high, and airliners rarely fly above 41,000ft, aircraft at cruise should actually aim the radar down slightly. This is because the best measurement of intensity is at the storm’s core, which is from the bottom of the storm (maybe 5,000ft) to the freezing level, which sits at about 15,000ft high. This will give the best radar returns and indication of storm strength. If the pilot aims the radar down too low, it will only show rainfall under the base (if any even exists at that time). If the pilot aims it too high above that height, where the moisture will be freezing, the radar signal will scatter off of the ice crystals, offering unreliable returns. The exception to this is if the storm is throwing wet hail very high.

Using this tool, pilots can ask ATC for deviations, usually by requesting to fly direct to a certain point or a change in 20 or 30 degrees in a particular direction.

Thunderstorms are no joke when it comes to flying. Thankfully, aviation history and the tireless efforts of the NTSB and the FAA on the regulatory side, along with talented and well-trained flight crews, Dispatchers and Air Traffic Controllers on the day-to-day implementation side, have become a well-oiled machine that keeps you safe. The next time you have a drink on a flight, toast to the many men and women who have your safety as their number one priority at that very moment.

Phil Derner founded NYCAviation in 2003. A lifetime aviation enthusiast that grew up across the water from La Guardia Airport, Phil has a background in online advertising and aviation experience as a Loadmaster, Operations Controller and Flight Dispatcher. You can reach him by email or follow him on Twitter @PhilDernerJr.