It goes without saying that the runway is the most critical area at an airport. Runways at major airports handle hundreds of thousands of takeoffs and landings per year, with aircraft weighing hundreds of tons moving on and off the pavement on a daily basis. Given the circumstances, these pavements need to provide a firm, stable and durable surface through all weather conditions that can adequately support the heavy loads imposed by the airplanes that use them.

Planning for the construction of a new runway begins years before the first bit of soil is dug up. The length, width and strength is dependent on the type of airport (such as a general aviation field or a major commercial airport), the size of aircraft most commonly served and the current volume of traffic on an annual basis, as well as forecast traffic volumes for future years. In terms of where the runway is located, consideration is given to the condition of the soil that will eventually form the subbase which supports the pavement. Borings are taken to obtain samples of the soil to determine its condition. If the soil is unstable, it would mean the pavement would have to be thicker to better distribute the loads that will be imposed on it.

The next consideration is the material used. At most airports, runways are constructed of man-made material, usually asphalt, concrete or a combination of both. The choice of pavement material comes down to local ground conditions, the type of aircraft using the facility and cost. Concrete is widely used at major commercial airports. Although it’s more costly than asphalt, a full concrete surface is more durable and has a longer lifespan.

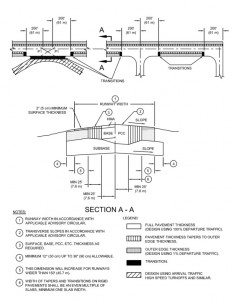

In the U.S., runway pavements are designed in accordance with FAA Advisory Circular 150/5230-6E “Airport Pavement Design and Evaluation.” During the runway design phase, a representative design aircraft is selected by analyzing the weight and number of operations of all the aircraft types that will be using the runway. The design aircraft is usually not necessarily the heaviest aircraft using the airport but rather the type requiring the thickest pavement given its landing gear layout and weight distribution. For purposes of the analysis, the operations of all the aircraft types at the airport are converted into equivalent operations of the selected design aircraft. These operations are then used to calculate the required thickness of the pavement. Pavement thickness varies from airport to airport, with commercial airports serving heavy aircraft having runway surfaces with a thickness between 10 inches and 4 ft., including the subgrade. Once the runway surface has been paved, it is grooved to allow for water to drain, minimizing the risk of aircraft hydroplaning following heavy rain.

Airport pavement strength is assessed utilizing the Aircraft Classification Number–Pavement Classification Number (ACN–PCN) method introduced by the International Civil Aviation Organization in the early ’80’s. All public use runways have a gross weight and a PCN value assigned to them. This numerical value indicates the load carrying capacity of the pavement in general terms. The ACN is assigned to every aircraft over 12,500 pounds to express its effect on pavement. The aircraft manufacturer computes the ACN based on the aircraft’s maximum aft center of gravity, maximum ramp weight, wheel spacing and tire pressure. The ACN also takes the subgrade strength of the pavement into consideration. Subgrade strength is divided into four categories: High (A), Medium (B), Low (C) and Ultra Low (D). Tire pressure is categorized in a similar manner as High (W), Medium (X), Low (Y) and Ultra Low (Z).

The PCN is determined by one of two methods, the aircraft method (U), or the technical method (T). The aircraft method simply determines the PCN value as the ACN of the largest aircraft permitted at the facility. The technical method derives the PCN value from the frequency of operations, permissible stress levels, landing gear type and the maximum gross weights that can be allowed on that particular runway. All together, the PCN is reported as a five part code: numerical PCN value, pavement type, subgrade category, allowable tire pressure and the method used to determine the PCN. Combining both the PCN with ACN gives airport and aircraft operators a good sense of the runway pavement’s capability, as well as what aircraft can be handled by that runway on a regular basis. For example, JFK’s Runway 13R/31L has a PCN of 98 /R/B/W/T, meaning it has a bearing strength of 98, has a rigid surface (R), with a medium subgrade strength (B), can accommodate any tire pressure (W), and the PCN was calculated using the technical method (T). For reference, the largest aircraft serving JFK – the A380 – has an ACN of 68. No coincidence as Runway 13R/31L was rehabilitated to accommodate the super jumbo.

There may be times when the pavement’s classification may be exceeded. Examples are a heavy wide-body aircraft making a rare visit at an airport that typically does not receive such aircraft. While the aircraft’s weight and ACN may be in excess of the runway’s PCN, the pavement wouldn’t necessarily experience a sudden failure. However if the aircraft exceeds the PCN by a wide margin, or becomes a regular visitor to the airport, problems may arise. An extreme example of this was in 2013 when a Boeing Dreamlifter inadvertently landed at Colonel James Jabara Airport (AAO) in Wichita, KS. The 600,000 lb. aircraft was 10 times heavier than what the airport’s concrete runway was designed to handle. After the Dreamlifter departed, engineers inspected the runway and found no visible damage, although given some time to settle coupled the freeze/thaw cycles of the winter, cracks may have formed that would need to be patched up.

The runway design and construction process usually takes somewhere between 2-4 years. Major airports typically build runways to last between 20-30 years before needing to be fully rehabilitated (though it doesn’t always work out that way). A runway rehab is effectively a reconstruction of the pavement and can be done two different ways. One way is to completely close the runway to air traffic while the pavement is rehabbed. Although cuts the total project time in half – or more – the capacity reduction can prove to be too high of a cost for the airport in terms of operational efficiency. In that case the airport may opt to close the runway at night and perform the work in sections. This allows the runway to be used during the daytime and early evening, though it can extend the project time to a year or more. Some airports, like Newark Liberty opt for a combination of the two, closing the runway for weeks or months at a time to perform major work, bookending it with nightly closures.

Runway pavements are routinely inspected for cracks, loose chunks, or other potential problems. When discovered, these problem spots get patched up as needed. Another regular maintenance item is rubber removal. After thousands of landings, rubber deposits from aircraft tires accumulate in the touchdown zone and can pose problems for runway friction and aircraft braking action. The FAA requires friction levels to be maintained at a certain level. Airports can opt to remove rubber using pressurized water, a chemical wash or via mechanical methods.

The world’s airports operate 24/7/365 receiving millions of flights per year. The strips of pavement that launch and receive these flights are built to stand-up to this constant demand.

Gabe Andino is an Associate Editor for NYCAviation.com, aviation enthusiast and airport management professional residing in New Jersey. Follow him on Twitter @OGAndino.