Over the past few days, the media has been buzzing about a writer’s account of near miss between two Boeing 757 aircraft. While it is true that there was a near miss on that day and time between two 757s, much of the information presented by the author is misleading or inaccurate (It should be noted that the author, Kevin Townsend, did a lot of research since this incident occurred, and he put special emphasis on just how safe the aviation industry is). Here is a look at what actually happened, as well as what didn’t happen.

Let us start with the proven facts. According to Kevin Townsend, the incident occurred early in the afternoon of April 25th over the Pacific Ocean just northeast of the Island of Hawaii. The author was aboard United Airlines flight 1205, a 757-300 flight between Kona and Los Angeles. Shortly after reaching cruising altitude of 33,000 feet that afternoon, the pilots of that flight were forced to take evasive maneuvers to avoid another 757 operated by US Airways that was flying in the opposite direction. All of that information is accurate, and the National Transportation Safety Board has begun an investigation into the cause of the near collision. However, that is where the facts begin to take a back seat to assumption and misinformation.

Perhaps the most eye catching bit of this account was that if both of these planes had indeed crashed, it would have been the deadliest ever. This was based on the author’s statement that the aircraft that he was on contained 295 passengers and the assumption that the other plane held an equal amount. If true, then there would have been a total of 590 people onboard the two planes, eclipsing the 583 people killed in the Tenerife Airport Disaster in 1977. In reality there were far fewer people onboard.

While we currently have no way of knowing just how many people were onboard, we do know how many passenger seats were on each jet. United Flight 1205 was operated that day by a 757-300 bearing the registration N57857. That aircraft has seats for 24 passengers in First Class and 192 in Economy, for a total of 216. Add in the necessary crew and there were roughly 223 people on the aircraft. Meanwhile the US Airways aircraft was a 757-200 flying between Phoenix and Kahului. That flight is typically operated with the airline’s domestically configured 757s, which have seats for 14 First Class passengers and 176 Economy Class passengers. Again, once we add in the necessary crew members, we see that there were seats for roughly 196 people on board. And all of that is assuming that these flights were full to begin with. Regardless of how many people were actually onboard, there is absolutely no way that either plane could have had anywhere near 295 people onboard.

If we were to assume that both aircraft had every passenger seat filled, along with a normal crew complement for a Hawaii to California flight, the actual, maximum number of people onboard both aircraft combined is much closer to 425. That number would have placed any potential accident in a distant third place in terms of the number of fatalities, behind both the Tenerife Airport Disaster and the 520 killed onboard Japan Airlines flight 123 in 1985.

The facts with regard to the passenger counts may seem like splitting hairs, because 425 people may still have perished, but the point is the sensationalist intent with the author’s way of words pertaining to his claims. Of course the headline, “Two Weeks Ago, I Almost Died in the Third Deadliest Plane Crash Ever,” isn’t nearly as attention grabbing. However, how close were those onboard to actually “almost dying?”

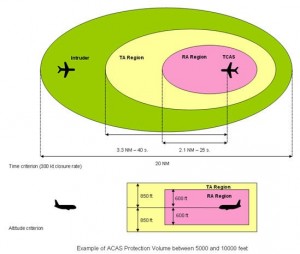

All aircraft with a maximum takeoff weight of 12,600 pounds or greater or which are designed to carry 19 or more passengers are required by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) to have a Traffic Collision Avoidance System (TCAS) installed onboard. This system monitors the transponders of other nearby aircraft for their position and altitude. If another airplane gets too close, the TCAS systems onboard both aircraft negotiate an avoidance maneuver. The corresponding directions, in a case like this a direction to either climb or descend, are then broadcast to the flight crews onboard each aircraft.

In this incident, the system seems to have worked exactly as it was supposed to. With two aircraft heading towards each other from opposite directions at the same altitude, one (United 1205) was instructed to descend in order to avoid the other aircraft. The best data that is publicly available shows that descent to have been roughly 600 feet in less than a minute. While we have no way of knowing what the actual rate of descent was, actions in response to a TCAS Resolution Advisory (RA) would typically be quite noticeable and sudden. And a 600 foot descent would be enough to maneuver the aircraft out of the Resolution Advisory window, as seen in the graphic to the left.

In this incident, the system seems to have worked exactly as it was supposed to. With two aircraft heading towards each other from opposite directions at the same altitude, one (United 1205) was instructed to descend in order to avoid the other aircraft. The best data that is publicly available shows that descent to have been roughly 600 feet in less than a minute. While we have no way of knowing what the actual rate of descent was, actions in response to a TCAS Resolution Advisory (RA) would typically be quite noticeable and sudden. And a 600 foot descent would be enough to maneuver the aircraft out of the Resolution Advisory window, as seen in the graphic to the left.

Another portion of his account is the explanation of how drastic of a maneuver the aircraft took. The CNN headline “Plane falls 600 feet in 60 seconds” plucked from the original account’s information makes little sense, since the typical descent rate for an airliner from cruising altitude is about 1,000 to 1,200 feet per minute (FPM). But if that dip took place in a much shorter amount of time, passengers likely did feel it, though it is highly doubtful that anything more than 0.5Gs would have been felt. This would be the equivalent of going over the top of a hill in a car, as opposed to the panic following a fighter jet maneuver that is implied in the original article. Even light turbulence can still make people respond audibly and cause a coffee pot to fall (as the writer indicated), and since no emergency was declared, we have little reason to think it was as violent as described. It should also be noted that no fellow passengers have joined Mr. Townsend to also claim a death-defying ride, even though people tend to jump on such bandwagons with their lawyers in tow.

As we further deconstruct the account of Mr. Townsend, it is helpful to know exactly who was involved here. In addition United Flight 1205, the author states that US Airways Flights 663 and 692 were in the vicinity at the time. However neither of those aircraft were involved in this incident. US Airways Flight 663 had passed off of United 1205’s left wing shortly before the near miss, at an altitude 1,000 feet above that of the United flight. Meanwhile, US Airways flight 692 was still more than 10 miles away laterally and 4,000 feet higher when the incident occurred. It was a third US Airways aircraft, operating Flight 432 from Phoenix to Kahului, which had the near miss with the United Airlines aircraft.

US Airways flight 432 was flying in almost the exact opposite direction of United Flight 1205, and both were cruising at 33,000 feet. While United was flying East at 610 miles per hour, US Airways was flying West at about 450 miles per hour. At a closing rate of roughly 1050 miles per hour, or a mile every 3.4 seconds, it would be extremely difficult for the pilots of either aircraft to see the other until it was too late. This is why TCAS is such a vital tool: it can detect an aircraft that poses a threat without it being seen by the pilots. Pilots are trained to obey TCAS RAs immediately, regardless of flight plans or the directions of air traffic controllers.

US Airways flight 432 was flying in almost the exact opposite direction of United Flight 1205, and both were cruising at 33,000 feet. While United was flying East at 610 miles per hour, US Airways was flying West at about 450 miles per hour. At a closing rate of roughly 1050 miles per hour, or a mile every 3.4 seconds, it would be extremely difficult for the pilots of either aircraft to see the other until it was too late. This is why TCAS is such a vital tool: it can detect an aircraft that poses a threat without it being seen by the pilots. Pilots are trained to obey TCAS RAs immediately, regardless of flight plans or the directions of air traffic controllers.

Automation: Sometimes It is The Problem, Other times It Is The Solution

Mr. Townsend goes on to assert that pilots are addicted to automation, and that is one thing that played a role in this incident. He isn’t wrong that automation onboard commercial airliners has been implicated as a factor in previous incidents such as Asiana 214’s crash in San Francisco last July. However it is really nothing more than that: a factor or stimulus. An over-reliance on automation can lead to a pilot not completing their most basic job function: flying the airplane. In the case of Asiana 214, the pilots made an assumption that the autothrottle system would maintain the proper speed throughout the descent. When the automation stopped working properly, the pilots failed to notice that this had occurred, resulting in a dangerously low airspeed which was a major cause of the crash. When it comes to working with automated systems, the old Russian proverb of “trust but verify” must be followed. Trust that the automation will do its job, but continuously verify that is in fact the case. At the end of the day, regardless of what computers are working, it has to be the pilots that are in charge.

So what role did reliance on automation play here? As best we can tell, United 1205 had leveled off at 33,000 feet about 10 minutes before the incident, while US Airways 432 had been cruising at 33,000 feet for a couple of hours already. Both aircraft had filed their flight plans with that cruising altitude set. Neither aircraft had made any drastic or unexpected course changes while enroute. Furthermore, the route that both aircraft were flying made sense given the destination of each flight. When a loss of separation did occur, TCAS detected it and issued a Resolution Advisory which successfully averted a potential disaster. In short, the automation here worked exactly as intended as best we can tell, with no obvious failures.

So what are we left with? It is possible that the controller responsible for that sector at Honolulu Center had a “deal”, and failed to keep the two airliners adequately separated. While it is not a common occurrence, these do happen occasionally. Typically they go unreported in the media for a number of days or even weeks, if they are reported on at all. A loss of separation in and of itself is just not typically a newsworthy event, nor is it typically publicized by the FAA or NTSB.

Finally, why were both eastbound and westbound aircraft travelling at the same altitude? The two aircraft flew their flightplans almost exactly as filed in opposite directions, until they met at a point in space over the Pacific. The incident occurred shortly after US Airways 432 had been handed off from the controllers at Oakland Oceanic (ODAPS) to the controllers at Honolulu Center (ZHN). However this hand-off does not seem to have occurred so close to the time of the incident that it should have played a role in the loss of separation. While Mr. Townsend’s statement about eastbound flights operating at odd-numbered flight levels and westbound flights operating at even-numbered flight levels is generally true, there are exceptions to this rule. The key in this case is that when an aircraft is, “in transition to/from or within Oceanic airspace where composite separation is authorized,” then that aircraft may operate at any ‘cardinal flight level.’ In other words, while flying over the Pacific, you can fly at any altitude, just as long as it is a multiple of 1,000. While both aircraft were within the airspace of ZHN, both were also transitioning into or out of oceanic airspace. So in this case, neither UA1205 or US432 were flying the “wrong way” as Mr. Townsend asserted.

There is no doubt that what occurred on the afternoon of April 25th off the coast of Hawaii was a serious incident. And, as the NTSB and FAA are currently doing, an investigation should be conducted in order to determine if any changes need to be made to the regulations in order to prevent a future accident. However, in this instance it would seem that all regulations and flight plans were followed precisely, and that the system that is in place to keep mid-air collisions from occurring worked as intended. Sure things got a bit scary for the passengers and crew onboard both aircraft for a few minutes, but that does not mean that the system is broken.

Ben Granucci, Associate Editor, is an aviation enthusiast and planespotter based in New York City. Growing up in Connecticut, he has had his eyes toward the sky for as long as he can remember. He can be reached on Twitter at @BLGranucci or through his blog at Landing-Lights.com

NYCAviation Founder Phil Derner Jr. contributed to this article.