If the airplanes are the life blood of an airport’s operation, the brains are its air traffic control tower. NYCAviation recently had a chance to visit one of the nation’s busiest control towers at Newark Liberty International Airport. The controllers’ responsibilities there include not only shepherding the airport’s own traffic through congested airspace, but monitoring and controlling a huge amount of air traffic that is passing through its designated airspace.

If the airplanes are the life blood of an airport’s operation, the brains are its air traffic control tower. NYCAviation recently had a chance to visit one of the nation’s busiest control towers at Newark Liberty International Airport. The controllers’ responsibilities there include not only shepherding the airport’s own traffic through congested airspace, but monitoring and controlling a huge amount of air traffic that is passing through its designated airspace.

When we arrived, we first cleared gate security and then were met by our host, local NATCA president Ray Adams. We proceeded into the base of the tower, and received a brief introduction to the facility from John Savarese, the facility’s Operations Manager. John explained to us the surprisingly vast scope of responsibility held by the controllers working there, which we were about to experience first hand upstairs in the tower cab. We headed over to the elevator and took it as high as it would go: the 23rd floor. Exiting, we were greeted not by the tower cab itself but by a small floor with facilities for the controllers to use while on their breaks. Given the level of stress that can come with controlling many aircraft in and out of a busy airspace, it was nice to see that accommodations were made to allow those working some amount of relaxation while on their breaks.

The supervisor’s console, on the right, overlooking the Ground and Local consoles. Photo by David Abbey.

After a few minutes we were on our way upstairs to experience the life of a tower controller first hand. As we climbed the stairs into the tower cab, it felt as if we were entering a subterranean command center not a glass-walled room atop a tower over 300 feet tall. The management of light — crucial for the preservation of the controllers vision — was carefully planned. Each window had double-layered and retractable light-dimming shades in a neutral grey tone, while lighting was tightly focused on specific areas and was capable of being carefully shuttered to only illuminate necessary areas. Even during mid-afternoon on a bright and sunny day, it was downright dark inside. Upon reaching the top, we entered the core of the tower cab where tower supervisors work. From here, the supervisor is in the middle of the action with remaining controller positions spread around the outer perimeter of the tower cab. Controllers can easily see and hear everything going on in the tower from this centrally located position, in addition to having individual displays which allow them to keep track of the big picture.

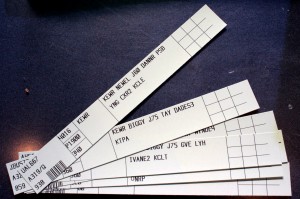

Following our introductions, we headed over to the clearance delivery console. This is where departing aircraft have their route clearances issued. Typically, a flight’s dispatcher will submit the flight plan, known as “the strip” (so named because of the strip of paper on which it is printed) to the clearance delivery controller. They in turn will approve (or deny in certain cases) the flight plan and the dispatcher will sent the approved plan to the aircraft where it will be loaded into the computer either automatically or manually depending on the airline. Meanwhile, the controller pops the printed strip into a reusable plastic holder. Once an aircraft pushes back from the gate, this strip is passed off to the ground controller. In cases where the flight plan needs to be amended such as during bad weather, the controller at this position must read the new clearance off to the crew for each flight that needs to be changed. This can be very time consuming and can quickly bog down the frequency used for clearances.

Because of the time consuming nature of delivering clearances orally, Newark’s tower is currently participating in a pilot program. Under the new system, clearances can be created and approved electronically by the controller in the tower. Then they are sent directly to the aircraft for the pilot’s approval while simultaneously being automatically loaded into the onboard computer. The pilot’s approval both notifies the controller and completes the process of loading the flight plan into the aircraft. This is a very small change during normal operations, however during times of bad weather when delays can build quickly this can greatly simplify and expedite the process. It is expected that once this pilot program is expanded to more airlines and aircraft, the number of times that an airplane has to be pulled out of line to wait its turn for a new clearance should be greatly reduced.

Multi-function display on its most common screen, showing runway configuration, current ATIS and METAR, among other information.

Next we toured the Class Bravo Airspace controller’s console. This position was formerly known as the Terminal Control Area (TCA). Somewhat surprisingly, this controller is the busiest in the entire facility, with responsibility for all flights below 2000 feet within a roughly eight nautical mile radius. The controllers at this position control between 300 and 600 of these general aviation movements through the airport’s airspace during the warm weather months, of which roughly 20 may land at Newark. Most of these flights are helicopters, primarily from tour operators operating up and down the Hudson River. Unlike what is required for fixed wing aircraft, the Class Bravo controller is only required to give traffic advisories to helicopters. Regardless of the legal requirements, our host said that he could not do that in good conscience. Most if not all of the controllers at the facility would provide the same services to helicopters as they would to airplanes including vectoring them through the airspace and providing separation in addition to calling out other air traffic. It was evident from speaking with the tower’s personnel that the Hudson River mid-air collision in 2009, which occurred within Newark’s airspace, had not been forgotten.

Life spent working in an air traffic control tower can go from routine to riveting in a matter of seconds. We were visiting during the annual UN General Assembly meeting, and a large no-fly zone was in place over midtown Manhattan. As we listened to the controller give clearances to helicopters operating in the area and then watched as they flew the routings they had been cleared for, suddenly things became very tense. An unknown aircraft, operating just outside of Newark’s airspace and therefore not in communication with the tower, had entered the restricted airspace. As it skirted the outer perimeter, the mood in our corner of the control tower changed from being laid back yet always professional, to laser focused on the task currently at hand. The controller at the console attempted repeatedly to raise the offending aircraft on the radio while still continuing to work various other aircraft through the airspace. Meanwhile our host and the tower’s supervisor focused on the radar scope, watching to make sure that the aircraft kept moving out of the no-fly zone and attempting to discover any clues about who the offender was. Very quickly, one controller noticed that the aircraft’s transponder indicated that it was a King Air and yet the speed with which it was travelling was significantly slower than that type would typically travel. Then a couple of minutes later, the tower’s activity quickly returned to normal. The aircraft was out of the restricted airspace and with no radio communications and an invalid transponder setting there was not much more that the controllers could do.

Finally, we headed over toward the Ground and Local consoles where we were given a couple of handsets and patched in to the radio system so that we could hear what was going on. Ground and Local each staffed by one controller at Newark. By comparison other major control towers, including LaGuradia and JFK in the New York area, may use a second controller at one or both of these positions at certain times. These two positions work very closely with each other by necessity as they both share responsibility for a large number of aircraft in a relatively small area. Each of these two positions both feeds aircraft to and clears aircraft from the other’s space. Arriving aircraft are received from the approach controller in another location, brought

in for a safe landing and cleared from the runways by the Local controller, who then hands them off to the Ground controller to maneuver them to either their ramp or gate depending on if there is a ramp controller (also in a different location). Similarly, departing aircraft are received from the ramp and guided along the taxiways to the appropriate runway. As they get near the end of the runway, the Ground controller hands them off to the Local controller who clears them onto the runway and then clears them to takeoff when it is safe and appropriate. Finally, they hand them off to the departure controller who is, like the approach controller, in a different location. Between the Ground and Local controllers stood another controller, the Cab Coordinator. Their job is to to liaise between the other two positions in order to make sure that each knew what the other was doing. They also monitor both consoles for

potential conflicts. Their ultimate goal is to keep the flow of aircraft moving while not allowing them to get too close to each other, particularly while they are passing between the two positions.

One item that we took particular note of was the “crash button” set off to the side of the Local controller’s console. Our host explained that in the event of an actual crash, pressing that button both sounds an alarm and opens the bay doors at the airport’s Aircraft Rescue and Fire Fighting facility. As anybody who has listened to the ATC transmissions after an on-airport crash can tell you, it is a very busy and stressful time for the controllers as aircraft need have their clearances cancelled and be vectored safely away from the airfield while the beginning of the emergency response is coordinated. Getting a jump start on the rescue crew’s response in a way that requires no words to be spoken in those first few

vital seconds is invaluable. Our host was careful to note that this button is only used when an actual crash has occurred and is not used for any other times when activation of the ARFF units is needed.

Having the chance to visit Newark’s control tower cab was an incredible experience that gave me a new level of appreciation for exactly what the job of a tower controller entails. The controllers that we met each had an obvious love for the job they did. While they all took it very seriously, it was easy to see that each of them wanted to be there. Their willingness to allow a small group inside to not only observe but to ask all the questions that we could think of was greatly appreciated. This willingness to share their world with others extends beyond just what they shared with us that day. Through their NATCA chapter, they are also available on Facebook and Twitter to share some of their experiences and to answer pretty much any question that a member of the public can think of.

Ben Granucci is a New York City based aviation enthusiast and planespotter. Growing up in Connecticut, he has had his eyes towards the sky for as long as he can remember. He can be reached on Twitter at @BLGranucci or through his blog at Landing-Lights.com