Flying to or from Europe is a pretty wild experience in itself. A trip that not long ago in human history could take up to two months by boat, can now be a 5 to 6 hour trip. But, even though you’re out the in middle of the ocean, and even with 4-engined aircraft and ETOPS capabilities (perhaps another article), it is not a direct line over to Europe for most. There are many planes vying for the same airspace, so routing rules exist.

North Atlantic Tracks (NAT) are roadways in the air that aircraft must follow to navigate through busy skies, similar to the airways that are over the United States and all over the world. Over the ocean, these tracks are built for aircraft that fly between 28,500 and 41,000 feet high.

Based on traffic demand, tracks are built for eastbound and westbound traffic waves. Labeled with letters such as V through Z, the eastbounds are active from 1:00GMT to 8:00GMT, and the westbounds are active from 11:30GMT to 19:30GMT, labelled with letters such as A through H.

The NATs are different every day, published in a collaborative effort from air traffic controllers on both sides of the ocean, and are built based on the jetstream and what is forecast to be optimal enroute winds. This, however, does not necessarily factor in the location of storms of forecast turbulence, so dispatchers (who build the routes and construct the flight plans) may opt avoid the tracks if they’d like, but there are many rules in doing so.

If you don’t like the NATs, you must avoid them altogether. You are not able to fly across a NAT at active altitudes, you are not allowed to exit the track once you’ve entered it, nor can you enter a track beyond the beginning of it. So to emphasize, if you don’t like the tracks that are published, you literally need to fly around the entire set of tracks, assuming you can carry the fuel. Or, if your aircraft can carry enough gas and airline management has no problem with the significantly slow enroute time, you are allowed to fly underneath the tracks.

FACT: The Concorde didn’t need to adhere to the NATs because it was altitude capable to easily fly over them, as high as 60,000ft.

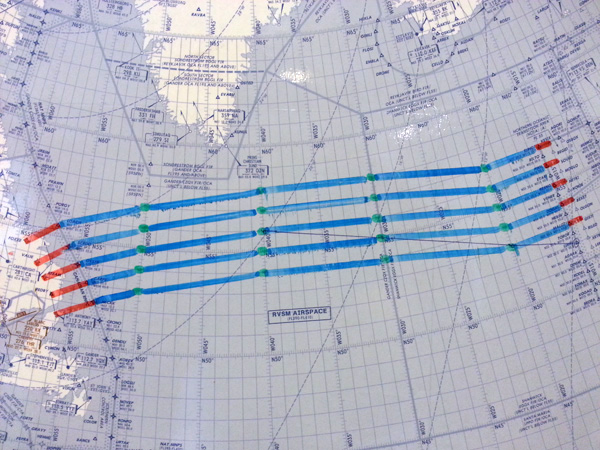

I plotted out the Eastbound NATs for July 10th on my wall chart (yes, we have navigational charts hanging on the walls, laminated for dry-erase use). The top one is Track V, and the letters go down to Z with each one.

Eastbound North Atlantic Tracks V through Z for July 10, 2013, are highlighted in blue.

On this day, the tracks are fairly basic and simple-looking, with no seemingly drastic turns. This is because there is simply no jetstream going over this region at the time, and without a jetstream, winds in the Summer tend to be quite mild. (Click here to see a North Atlantic Significant Weather Chart, with the green lines showing that the jetstream is far away from the North Atlantic flying region)

Getting onto and off of the tracks is just as important as the tracks themselves. Each side of the ocean has entry and exit points, almost like a gate to enter the airspace. Just off the coast of both Europe and Canada are many pairs of named waypoints that send you to/from the ocean. If you fly over one of the points, you must fly to its buddy point, which is intended to line everyone up before going oceanic or breaking off to whatever area of the new continent they intend.

The Canadian entry and exit pairs are shown in red.

The pairs are important for all Trans-Atlantic flying. Even if a flight is not riding on a NAT, the pairings must get followed. Aside from the ones highlighted in red on the examples given, you can see the other pairings either above of below, all of which are available for use regardless of active tracks, as long as you do not violate the rules of the tracks as well.

The European entry and exit pairs are shown in red.

The tracks are sent to airlines at the time of publishing, and are posted online for access as well. The tracks themselves are written out with the entry pair, the coordinates of the points across the ocean that form the track, and the exit point. Here is the published track for NAT V, or “North Atlantic Track Victor”.

V FOXXE LOACH 57/50 58/40 58/30 57/20 SUNOT KESIX

So Track V has the Foxxe-Loach exit pair over Canada, then the numbers indicate the latitude and longitude, meaning 57/50 is 57°N and 50°W, and so on. Then SUNOT-KESIX are the entry points into Europe for that track.

Here is a closer looks at some of the plotted coordinates.

The center portion of the active eastbound North Atlantic Tracks plotted out.

So if you’re at JFK watching the evening international departure push of all of those massive jets heading to Europe, you have a better idea of where and how they are navigated. The tracks keep aircraft separated and safe, which is important in an area that has no radar coverage for Air Traffic Control.

Wait…I did tell you that there’s no radar over the ocean, right? Well maybe I’ll save that for next time.

-Like this lesson? Is there another topic that you’d love for us to write a lesson on? Email [email protected] to share.

DISCLAIMER: This lesson is for entertainment only and is not officially sanctioned by the FAA or any worldwide aviation authority for the sake of guidance or performing flight operations.

Phil Derner founded NYCAviation in 2003. A lifetime aviation enthusiast that grew up across the water from La Guardia Airport, Phil has a background in online advertising and airline experience as a Loadmaster, Operations Controller and Flight Dispatcher. You can reach him at [email protected] or follow him on Twitter at @PhilDernerJr.